Sunday, December 10, 2006

Wednesday, November 01, 2006

Overwork? Lack of sleep?

Sunday, October 29, 2006

Baroque Cycle and Change

Unlike most of Stephenson's earlier works, the Cycle is set in the past, during the 17th and early 18th century, when the world was moving from one dominated by religion and aristocracy to one driven by science and economics. The characters include most of the prominent members of the Royal Society (Isaac Newton, Robert Boyle, Robert Hooke, etc.), Louis XIV of France, William I of Orange and James II of England. The fictional ones include vagabond Jack "Half-Cocked" Shaftoe, Eliza, a former harem slave turned duchess, and a smart but underachieving member of the Royal Society named Daniel Waterhouse. The action moves through India, North and South America, Europe and North Africa. A reviewer for the Telegraph put it best: you don't just read the Baroque Cycle, you move in and raise a family.

Like all good science fiction, the tension in Stephenson's stories comes not from prediction, but from responding to dramatic or catastrophic shifts in perception. That's why Jules Verne or H.G. Wells novels remain good reads, even if little of what they say have or will occur. It's about contemporary humans confronting a new world, one where the old rules no longer apply, and they must adapt.

The Cycle is about a time when almost all modern concepts in science, such as physics, computing and cryptography, first crop up, even if the inventors didn't yet have the resources (i.e., engines) to put all of them into practical use. At the same time, politics was being transformed by the rising power of the "Mobb," the common man, and nations were beginning to grasp the power of currencies and international trade. Battles were still fought with guns and swords, and obviously will continue to be, but economic warfare was already becoming crucial. A smart investor with some cash could bring down a government, then as now. Those several decades were the historical equivalent of a perfect storm.

Half the fun of reading such a novel is to put myself in some of the characters' places and imagine how I would respond, whether I would recognize the changes in time, or know how to take advantage of them. With Stephenson's story, we know what happens next. It took another 200 years before economists understood fully that money is a confidence trick. It isn't based on gold, but on the belief that a nation can generate the wealth to back it up. And we're still grappling with the implications of our understanding of the universe, and our relatively minor role in it.

We're also living in interesting times now: We have all of the world's knowledge at our fingertips. Anyone can write, film or record something and have it instantly read or viewed by a billion people. And, on the negative side, any tin-pot nut case can acquire the know-how to kill thousands. I wonder how long it will take us to fully grasp today's changes?

Monday, October 23, 2006

rly fun

"I went huntin. It was rly fun."

"What were you hunting?" I replied. "And did you kill one?"

"4 pheasants and partridges. I didn't kil. any but they (chris+his dad) got 3 pheasants + 1 partridge."

I'm sure trooping around the French countryside killing birds is improving his French...

Sunday, October 22, 2006

Free software

Free software is a bit like science. Scientists publish. The data is then ripped apart by other scientists. What holds up to scrutiny becomes the foundation for the next discovery. That process is the way, as Isaac Newton put it, that scientists "stand on the shoulders of giants." Few would argue that science lacks value, or that it would be worth more if kept secret.

Software used to work more like science, back when the commercial value was thought to lay purely with the hardware. Software (in source code form, so that you could see how it worked) was freely distributed and shared. It was when the tide was turning toward closed, commercial software that Richard Stallman, a programmer at MIT, formed the Free Software Foundation. His aim was to create everything you need to use computers -- the operating system, the applications, etc. -- in a free and open way. His genius was to use copyright law to ensure that the software stays free. The FSF's General Public License gives you the right to use the software (for any purpose), share it without anyone, view the source code and modify it. The catch is that you can't remove any of those rights. If you modify the software and distribute it, you have to pass on the same rights. That restriction is enforced by copyright law, which gives the creator of the software the ability to dictate the terms of use. In this case, the terms are the opposite of the usual restrictions ("all rights reserved"), hence the GPL's nickname: copyleft. There are several other free software licenses, but the basic concept is usually the same.

One point of confusion comes from the limitations of the English language. One of the rights isn't that the software should be free, as in no cost. Free software means freedom. You're perfectly entitled to sell your modifications, and people do, but the Internet and its easy copying has led nowadays to most free software developers making their money by selling their skills (e.g., getting a job with a company that uses free software) or by offering technical support (such as Red Hat Inc. or Canonical Ltd.). What's interesting about free software is that the economic incentives, plus "copyleft," ensure that the general level of quality rises. If you're looking to sell your skills, you're going to want to make your work (free for anyone to see) as high quality as possible. If you are selling technical support, you better make your software as trouble-free as possible, to lower your costs. And, in both cases, you're obligated to share your work with everyone else. But what I found most interesting is that much of the work, maybe the majority, is done by people who get no economic benefit whatsoever. They do it because they find the work engaging and they believe in freedom.

Whatever the motivation, the system works, and has generated billions of dollars in market value. Every time you use Google or Amazon, you're using free software. The majority of the Internet is built with it. As thousands of developer tweak, twiddle and fix, that work goes back to the community. Everyone benefits.

As an end user, however, benefiting used to be hard. I remember starting with GNU/Linux, a combination of the Free Software Foundation's applications and a free operating system, back in 1993. Hardware support was limited and it was a real effort to learn. Nowadays, it is so easy it's almost boring. I currently use Ubuntu, one of many "distributions" of GNU/Linux, which handle the work of combining the applications and the operating system into a usable package. A new version is due out this week (Oct. 26). You can try it before installing it by running the software from a CD. Wireless networking can still a be bit tricky, but almost anything else I throw at it (digital cameras, iPods, etc.) is handled with aplomb. Today, you don't even need to use a free operating system to try free software: just try Firefox.

I'm not against commercial software. I use Windows for 10 hours a day. It's fine. But I do believe free software will win out in the end, just as open science won out over alchemy, which was also based on secrecy. What holds back most people from using free software is the subject of another post, but basically it's responsibility. People don't want to take it. Using free software when no one else you know is means taking responsibility for your own computer. People would much rather just let Microsoft (or whoever) handle it. It gives them someone to blame. It's why my children's schools all sign expensive contracts with Microsoft Solution Providers. They don't want the responsibility. I can understand that and feel no compunction to "evangelize."

But personally, 25 years of using computers is enough to demonstrate that commercial companies don't give a fig about me. I'm only valuable to them if I keep on buying. Putting important information in their hands -- such as your photos, important documents and music -- is nuts. I've pumped out a lot of information into proprietary applications that is no longer accessible. I've paid a lot of money just to keep what I have. I'm motivated to take responsibility, and to help our where I can. I report bugs, test new software and helping others when asked. It's the least I can do, and in the meantime I get to watch a revolution unfold.

Saturday, October 21, 2006

Goals

I don't believe "affirmations" are anything new. They were probably invented around the same time as stone tools. People used to call it prayer. Repeating something often enough, in a positive way, obviously has an affect. It keeps the goals in the forefront of our mind and alert to opportunities. Adams certainly has a long track record of achieving his.

But Adams's post brought up a troubling thought: I don't have any idea what I would write down as goals. I have wishes -- I want every member of the family to be happy, for example -- but those are mostly out of my hands, more the domain of prayer than affirmations.

So what would I write down, assuming (and this is a big if) I'd have the patience and the self discipline to do it several times a day? On this side of 40, the question has become more difficult. I wanted to be a journalist and I succeeded. I could always be better, of course, but I've definitely achieved that one. Marriage, family, buy a home? Check. Travel and live abroad? Doing that. Most people at this stage just carry on as before. I'd rather have a more definite destination in mind for the second half of my life. It shouldn't just be a 40-year winding down.

Financially, I don't necessarily want to be rich, but I do want the flexibility to trade money for time. I want to be able to work less and spend more of my time with the family, to pursue my interests, to get involved in causes I'm passionate about. At the moment, I spend the great majority of my waking hours on making money, all of which goes right out the door again to house, feed, clothe and entertain a family of seven in one of the most expensive cities in the world. The rest of the time is spent taking care of -- fixing, filling, emptying, watching, listening to or cleaning -- all of that accumulated "stuff" that seems to gather around us like dust bunnies. Life is upside down. The important is crowded out by the mundane.

Of course, it's not really a finance issue. If I were richer, the ratio of my time spent on "taking care of stuff" and on food and shelter would just shift a bit. It's really about priorities -- setting them and sticking to them -- and then I'm back to the problem of goals.

I started out writing this thinking I'll just list some, but I'm realizing now that it isn't that easy. I'm already making choices -- every time I buy more stuff or stay late at the office -- but with no definite plan. I'm just going with the flow, unsure of where it's taking me.

Answering that question is tougher than I thought -- a worthy goal.

Friday, October 13, 2006

Child Prodigies

One of my favorite writers, Malcolm Gladwell , gave a speech, summarized here, that's really worth reading on the "myth of prodigy." It's a good reminder that I need to worry less if not all my children are at the top of the class. A snippet:

Gladwell cited a mid-1980s study (Genius Revisited) of adults who had attended New York City’s prestigious Hunter College Elementary School, which only admits children with an IQ of 155 or above. Hunter College was founded in the 1920s to be a training ground for the country’s future intellectual elite. Yet the fate of its child-geniuses was, well, “simply okay.” Thirty years down the road, the Hunter alums in the study were all doing pretty well, were reasonably well adjusted and happy, and most had good jobs and many had graduate degrees. But Gladwell was struck by what he called the “disappointed tone of the book”: None of the Hunter alums were superstars or Nobel- or Pulitzer-prize winners; there were no people who were nationally known in their fields. “These were genius kids but they were not genius adults.”Now look at it the other way:

The other way to look at precocity is of course to work backward — to look at adult geniuses and see what they were like as kids. A number of studies have taken this approach, Gladwell said, and they find a similar pattern. A study of 200 highly accomplished adults found that just 34 percent had been considered in any way precocious as children. He also read a long list of historical geniuses who had been notably undistinguished as children — a list including Copernicus, Rembrandt, Bach, Newton, Beethoven, Kant, and Leonardo Da Vinci (“that famous code-maker”). “None of [them] would have made it into Hunter College,” Gladwell observed.In fact, being considered a child prodigy can be a handicap, Gladwell says. The one "poster child" for precociousness, Mozart, in fact, isn't. What he did, perhaps via a pushy father, was work his tail off.

Here in the U.K., even more so than in the U.S., the focus is on spotting talent early, and giving up on the rest quickly. You're pegged as university-bound at 11 and football-player material at 7 or 8. Students here have to make drastic choices on their future at 13 or 14, deciding whether to stick with maths and science, or give up on foreign languages. At that age, I'd be pegged as a non-achiever and relegated to stopping after high school (if I even made it that far).

My advice to my kids is to keep your options open, with basic and broad subjects, and don't get pegged. It's hard work, like swimming upstream. The schools want you to decide, or they'll decide for you. I need to send a few of those teachers a copy of Gladwell's speech.

In the meantime, though, all of my kids are more socially adjusted and doing better at school than I ever did. Their struggles are minor, not major. They'll be OK.

Cures for the Common Cold

With little else to do, I've been thinking about all of the proposed cures. My mother's latest preventative, if not cure, is to take a protein drink a day. Yes, the same stuff bodybuilders drink to "bulk up." My very thin mother needs to bulk up, I don't. My wife Theresa swears by Echinacea, an herbal remedy. I believed it worked if I started taking it just at the beginning of a cold, but it hasn't touched this one as far as I can tell. Vitamin C is one of those cures that only seems to work if you believe it does, same with Zinc. The Wikipedia article on the Cold lists a few more, albeit similarly iffy, cures.

For now, the only cure I've found is to sleep through it.

Thursday, October 12, 2006

Family at a Distance

I was home over the weekend for my sister Dara's birthday and, finally, got a few of the family members on Skype. We haven't tried to use it yet, but I'm hopeful it'll let me hear their voices now and again. At the moment, we see each other only every couple of years, at most. I met my youngest nephew for the first time and reacquainted myself with the older ones, so that I'd at least recognize them if I met them on the street. I also got a quick top-up on Americana -- watching a school football game, in person, and a baseball game or two on my father's giant-screen TV.

But the most important thing I've learned in the last two trips to the U.S. (the prior one being for my mother-in-law's funeral) is that I need to do more on my end to keep in touch. Letting this blog languish isn't helping, nor am I going out of my way to email. So, for the time being, I'm back to posting and will try to keep it up, even if I don't have anything brilliant to say.

Thursday, August 31, 2006

A life well lived

Life comes in waves of weddings, baptisms and, finally, funerals. They're our periodic reminders of what life is about.

The impact of Elaine, my mother-in-law, was evident at her funeral last week. Nine daughters, 38 grandchildren and 20 great grandchildren, who all owe their very existence to her, are just the beginning. A lifetime of involvement in the community made a deep impression on the world. Her departure leaves a void, especially for her husband, with whom she shared more than 64 years.

But what was evident in the family gatherings after the funeral is that Elaine's love, her compassion, her commitment to the family and community and her humor live on in her daughters, grandchildren, great-grandchildren and even her friends. That's the legacy of a life well lived.

Tuesday, June 27, 2006

Second Life

It's the name of Second Life that put me off. I don't have time for my first life, let alone another one. But if something doesn't grab me initially, it's usually because I don't know enough about it. And there's no doubt that this is the future, or something very like it. I need to learn more.

Second Life is more of a place than a game. It's created by the people who use it. Participants make and animate a graphical representation of themselves, called avatars, and walk, fly, drive around a large continent and surrounding islands, chatting with others, building or buying things, and almost anything else you can imagine.

Although this metaphor will probably offend anyone remotely connected to Second Life, the most accurate way of describing the whole experience is that it's like playing with dolls. Mind you, these are very cool dolls. They can do and say anything at all. You build your own accessories, such as a house and furniture, clothes, car. You can also buy any of the above, at miles of shops in the world itself.

The imagination of some of the residents is impressive. One avatar I met over the weekend was a cartoon rabbit. He was wearing a t-shirt that changed its slogan every minute or so ("There's no place like 127.0.0.1" "Touch my carrot"). I've also met a dinosaur, a sphinx and a Luke Skywalker look-alike, complete with storm trooper outfit, light saber and R2D2.

My avatar is vaguely a copy of me, albeit thinner and with better hair -- no imagination! I haven't progressed far with making accessories, either. The best I've been able to create was the beginnings of a snowman. While I was struggling to do that, someone next to me was practicing with a motorcycle. She drove away before I got my snowman's head on straight. With built-in 3D designing software and scripting language, or using an external free application such as Blender, there doesn't seem to be too much you can't do.

Although there are no clear goals in Second Life, participants seem to treat it like a game of Life. They aim to sustain and grow their character over a long period, master the environment, create an interesting alter-ego and get "rich." Getting rich is at least possible. Second Life may be virtual, but the economy is real. The currency, called Linden dollars, has a floating exchange rate against the U.S. variety. The rate is currently about 250 to 1, so you'd have to be the Second Life equivalent of Bill Gates to be rich in reality.

You get 250 Linden dollars when you join. You own, and can sell, anything you make. Don't have much money? Get a job. The most skilled can work as a builder, the lucky as a fashion model for one of the many clothes designers. Residents who sign up for a monthly plan (instead of the free membership) get a plot of land to start off with, giving them a leg up onto Second Life's property ladder. Monthly subscribers also get a L$500 weekly stipend.

I find the culture a bit baffling, even after a few days. It seems to be bad manners to ask about, or even reveal, much about your "first life." To view someone's profile, you right-click on their avatar. Although there's a section for describing who you are outside of Second Life, I'm the only one who seems to have anything in there. That brings up an interesting question. What do you talk about? I like meeting people, not avatars. I don't need a name, age, address and social security number -- I just want to know where they are from (generally), what attracted them to Second Life, what work they do. I also want to know how old they are. How rare are 43-year-old residents? The main topic of conversation seems to be Second Life, or what accessories you have, or what you're building. As a newbie, I don't have much to contribute to the discussion.

Finding people and things to do and see is harder than I thought. Although there are a quarter of a million residents and several thousand online at any given time, the place is huge. There are several ways to get around. You can just walk or, with a keystroke, fly, just like in dreams. You can also teleport from one place to the next by clicking on a spot on the map or choosing a location from a list.

When I just wandered or flew around, I ended up finding mostly dull shops and casinos. My initial impression was that Second Life is a giant shopping mall with almost no one in it. I also ran into a lot of "mature" areas. I had no idea that anyone older than 12 got their kicks out of posing their "Ken" and "Barbie" into erotic poses. I don't feel enriched by this discovery. But once I figured out how to find "events" and centers catering to newbies, the experience has picked up a bit. I found a couple of wonderful parks, art galleries and "sandboxes," where you can try building things.

I'm also starting to understand the advantage of Second Life over more traditional text- or even audio-based communication on the Internet. You can use four of your five senses, making communication a lot richer and easier to assimilate. I can spot groups of people talking from a distance, for example, and swoop in to join the conversation. There are cinemas (videos), concerts and dance clubs. People have organized presentations in Second Life and play their own selection of music at their "house" or shop.

You also get a richer idea of a person by the avatar they choose. It doesn't tell anything about the more superficial aspects -- what they do or where they are from -- but you definitely get a quick impression of their personality and (possibly) world view.

I still don't have much time for a "second life," but as I get the hang of it, it's seems worthwhile dropping in when I can. I'm "Eamonn Supplee" (you have a limited number of surnames to choose from). Stop by and say hello!

Monday, May 15, 2006

Dorodango

This is my first, very poor attempt at making a dorodango. It's not supposed to look this rough (I used soil that was too gritty), but I was still very impressed that it worked at all. You can't tell from the photo, but the ball is rock-hard and heavy. It looks exactly as if I found a nearly perfectly round rock and gave it several coats of enamel. I only dimly remembered reading about the Japanese art of making these things (I read the linked Web page a year ago), but while watching my son play baseball it occurred to me that the soil at baseball fields, with its mixture of sand and clay, would probably be perfect for making one. I just threw some water on the soil, formed a ball, and started polishing using dry soil. This is the result after a hour and a half or so. It would have come out smooth if I had sifted out the pebbles, which I may try next time.

Friday, May 12, 2006

Another year

DSCF0002.JPG

Originally uploaded by ailishsul.

The beer, the TV remote control and lots of candles on the cake... The parallels with Homer Simpson are becoming scary.

Wednesday, May 10, 2006

Roman Holiday

Theresa looking out over the forum

Originally uploaded by Eamonn_Sullivan.

Theresa and I are back from a short trip to Rome, our first. The city wasn't high on my list of places to see. Iceland was considerably higher, to give you an idea. But I thoroughly enjoyed it.

As usual, I set out to learn the language before we went and didn't get far. My excuse this time was that my iPod died -- complete hard drive failure. That happened about three days into my attempt to get through an Italian audio course and it meant I had to listen to it in the car (30 minutes a month, approximately) instead of the tube (2.5 hours a day). I ended up barely knowing how to say non parlo italiano by the time we arrived.

We saw the usual sights -- Vatican, Coloseum, the Roman Forum (that's the Arch of Septimius Severus behind Theresa). We walked about 10 miles on the first day, so had to take a break on the second and hang around a huge public park near the hotel, filled with local families and some sort of African festival. We ended the day at a wonderful little trattoria (family restaurant) in an alley in the Trastevere neighborhood.

On the third (and final) day, we spent most of it in at the Vatican museum and St. Peter's. The museum was fabulous, but the crowd going to see the Sistine Chapel wasn't so fab. We felt like cows being herded. We quickly broke off and made our way to the quieter exhibits. For lunch, we ate at a pizzeria recommended by a colleague at work. We ended the evening at a more upscale restaurant near our hotel for a complete, six-course meal. It was wonderful, but I feel like I brought some of Rome home with me, around my middle...

The complete set of photos from the trip is here.

Tuesday, April 18, 2006

Quiet

A more fruitful approach is to integrate quiet time into daily life, like regular exercise. My first encounter with that idea was the Rule of St. Benedict, a guide for monastic life written in the sixth century. I became familiar with it while attending Saint Anselm College in New Hampshire, which is run by Benedictine monks.

You don't have to be religious to appreciate the central theme of the Rule: balance. The monks' days are divide into manual labor, quiet contemplation, socializing and service to others. The balance still fits well, even after 800 years. Labor was set at about six hours a day, which is bang on for productive work, in my experience. Sufficient food and sleep was considered important and the rule has little of the gratuitous austerities then fashionable. It was written for real human beings, exhorts them to be human, and it's still going strong.

Alas, modern life often isn't very amenable to balance. I may only be truly productive for six or seven hours a day, but my bosses don't want to hear that. So I'm in the office, typically 11 or 12 hours a day, eating both breakfast and lunch at my desk. Couple that with about 2 1/2 hours commuting, seven hours or so of sleeping, and that leaves about two hours a day to accomplish everything else.

That doesn't mean I can't integrate quiet time in my life, of course, but it does mean I have to make trade-offs that are difficult. I already spend too little time with my family and don't exercise enough, for example. I'm also an insatiable student. I've spent many hours of that free time this year learning Common Lisp, just for the heck of it. So, what goes? And when? It's an ongoing struggle.

Another approach is to make whatever I'm doing a quiet meditation. This idea is a heck of a lot older than the Rule of St. Benedict, stretching back at least to Buddhism. Basically, it's the belief that life is what is happening right now and that most of us wander through existence in a dream-like state, worrying about the future, dwelling on the past or feeling deprived of some imagined need, such as money or time. Those who reach enlightenment, Buddhists say, are fully present, fully aware of life, and at peace.

That idea is behind the "mindfulness" approach that has taken off lately. See here, for just a very recent example. And it's no wonder. "Continuous partial attention" is the norm today. We're always doing several things at once, while planning our next steps and worrying about the previous one.

Escaping from this is so hard that people try to find easy short cuts. One is extreme sports, which force you to be fully here, fully focused on the present moment, more alive. But thrill-seeking is a cheap, shallow copy of what an enlightened, mindful Zen Master can accomplish while washing the dishes, sweeping the floor or simply sitting under a tree. What the parachutist accomplishes is more basic -- a survival mode, an adrenalin-fueled rush. What the mindful can accomplish, even while skydiving, is to be fully human.

Learning to quiet that constant, inane chatter in our heads takes practice, however. And fighting it doesn't work. Try telling yourself to think of nothing... The way Zen Masters do it is to develop a level of detachment, so they can observe themselves wandering and gently bring their minds back.

Although gaining that skill takes a lifetime -- or several, according to Buddhists -- even the first faltering steps are worthwhile. Just yesterday, I was dwelling on all of the things that are hanging over my head, such as the big news events coming up at work that I must prepare for, the seemingly endless list of repairs needed on the house and the worries about my wife and children. And then I looked up and paid attention to what was happening around me. I was walking the dog, with my beautiful wife, on a gorgeous, sunny day. The birds were singing, the blossoms blooming and the only thing that needed doing, right now, was to be here and enjoy the walk.

Even in my busiest, most hectic moments, the contrast between my harried mind and the what is actually happening is stark. I may be jamming under a very tight deadline, with multiple people demanding my attention at once, but the present moment consists of making the sentence under my cursor read well, with no errors or awkward phrases. The present moment is always quiet, always peaceful.

I'd like to try a day of silence sometime, maybe 24 hours on a shoreline with a pup tent and a sleeping bag. But I suspect it wouldn't improve my life as much as the essay writer thinks. A better approach would be to just pay attention to the quiet around me. Right now.

Tags: Life

Saturday, April 08, 2006

Sunday, January 29, 2006

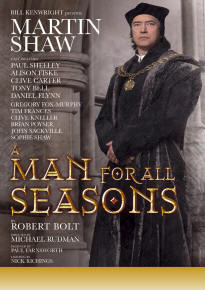

A Man for All Seasons

We went to see A Man for All Seasons with Martin Shaw last night with my parents, who are visiting from the U.S. It was excellent. I only dimly remember the film and never saw it on stage before, but my father watched the play in the early 1960s, with Paul Scofield, and he enjoyed this production as well. If you get a chance, catch it before it closes on April 1st.

My favorite part of the play is when More defends the law against the ultimate in "the end justifies the means" arguments. The character Roper and More's daughter Alice beseech More to have his eventual betrayer arrested before he leaves the house, even if he has to make up some pretext. More argues that doing that would be a very bad idea:

Alice: While you talk, he's gone!

More: And go he should, if he was the Devil himself, until he broke the law!

Roper: So now you'd give the Devil benefit of law!

More: Yes. What would you do? Cut a great road through the law to get after the Devil?

Roper: I'd cut down every law in England to do that!

More: Oh? And when the last law was down, and the Devil turned round on you - where would you hide, Roper, the laws all being flat? This country's planted thick with laws from coast to coast - man's laws, not God's - and if you cut them down - and you're just the man to do it - d'you really think you could stand upright in the winds that would blow then? Yes, I'd give the Devil benefit of law, for my own safety's sake.

Roper's sentiment is as strong as ever. Terrorism, or whatever the evil du jour, may seem to justify sweeping away inconvenient laws, as long as it makes us safer. But it has the opposite effect in the long run.

Tags: Theater, Legal

Sunday, January 22, 2006

Programming and Writing

I was speaking to a fellow editor recently and confessed my secret: I program computers for fun.

"Are you sure you're in the right job," she asks.

Yes, I reply, because programming and writing, especially non-fiction writing, are essentially identical skills. I believe that's why there are many good programmers who are also good writers -- Paul Graham, just to take one example. That we don't see too many examples of the reverse is because few writers understand the symmetry.

Both aim to convey information -- ideas, images, numbers and text -- in the most concise and efficient way possible. And both achieve beauty when they succeed. I wouldn't compare programming to Shakespeare, but there's not much separating a good software application from a well-written news story or essay. Software conveys information to a computer initially, while the written word is read directly by a human reader. But even that difference is just a distraction. The ultimate target of both is a person.

I've written for a living and programmed for fun for at least 20 years now and find that practice in one improves the other. Neither can be done well unless I'm thinking very clearly about the problem I'm trying to solve or the ideas I want to convey. Building logically from one point to another, in the simplest, clearest way possible makes good source code and good writing.

And just as learning different human languages can make you a better writer, learning other computer languages makes you a better programmer. I'm absolutely hopeless at learning human languages, and struggle enough with English to keep me well occupied. I studied French for years and still can't ask for directions or understand the answer. I don't remember much about the Latin I studied in High School, nor the Russian I spent two years wrestling with at university, but I do believe I've received benefits from them. I may not remember many specifics, but I do remember the ideas, recognize a Latin root or two and have observed the pluses and minuses of their different approaches. A phonetic alphabet (Russian) is a good thing, for example, as is precision in the choice of words.

I can't claim to be any better at computer languages, but at least I pick them up faster. I've programmed in Basic, Pascal, Fortran, C, C++, Java, Perl, Visual Basic and lots of different application-specific macro languages. My current favorite is Python, and I've written fairly complex graphical programs in it. As with the human languages, I've absorbed them to varying degrees. I can still pick up a Basic program, even though I haven't programmed in the language in any serious way since the Apple IIe, while I would have to learn C++ and Java again from scratch. And, again, I've benefitted from each, because each has a unique way of approaching and solving problems.

Since the beginning of the year I've also been putting in some serious effort into learning Common Lisp, so I'll use that to illustrate some of the benefits.

Lisp has been compared to Latin. In computer terms, it's certainly as old as Latin, dating back to the mid 1950s. But I think it's closer to a language with a completely different alphabet or wholly unfamiliar grammar, like Greek, Japanese or Hebrew. Unlike most modern languages, which are based on a predecessor known as Algol, Lisp isn't written in a way that would look familiar to most people.

The Pythagorean Theorem --

c = √(a²+b²)

-- might be written in a Algol-derived language such as Python, like this:

c = sqrt(a**2 + b**2)

Most people would find that at least familiar, once told that sqrt means square root and ** means exponent, anyway.

In Lisp, however, one way to write the same thing might be:

(setf c (sqrt (+ (* a a) (* b b))))

The inside-out style is definitely unfamiliar, but it doesn't take too many bouts with really hairy algebra or tricky text manipulation to understand that it is more efficient for some problems. There are many tasks that would take several steps in an Algol language, but can be solved with a tight one-liner in Lisp that, once you get used to it, is still readable. Learning a new language, in other words, is forcing me to think differently, out of the box.

Another benefit of putting effort into both disciplines is that it puts you in charge of two essentials of the modern world: communications and computers. The latter is getting as ubiquitous and as necessary as the former. Just as illiteracy can turn a free human being into a slave, computer ignorance will make you steadily less and less in control of your life in the next decades. Kids today are being taught nothing about computers in school except how to run Word and Excel. Who's the master in that relationship? It isn't the student. Programming has made me as confident in wielding a computer as the written word. (Read: not very, but I'm learning.)

The original question -- about whether I'm sure I'm in the right job -- assumes a divide between the sciences and the liberal arts, math and art, computers and words. I don't think it exists. I'm proud to be interested in both.

And, anyway, it's a lot more interesting than doing a crossword puzzle.

Tags: Programming, Writing